Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum things to do, attractions, restaurants, events info and trip planning

Basic Info

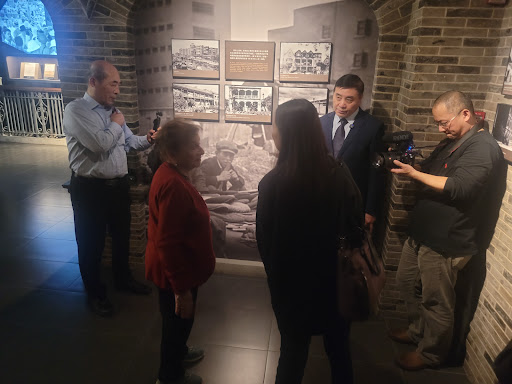

Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum

62 Changyang Rd, Hongkou District, Shanghai, China, 200086

4.6(77)

Open 24 hours

tickets

Save

spot

spot

Ratings & Description

Info

The Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum is a museum commemorating the Jewish refugees who lived in Shanghai during World War II after fleeing Europe to escape the Holocaust. It is located at the former Ohel Moshe or Moishe Synagogue, in the Tilanqiao Historic Area of Hongkou district, Shanghai, China.

Cultural

Accessibility

Family friendly

attractions: Huoshan Park (North Gate), Xiahai Temple, North Bund Green Land, 宝地广场, restaurants: Baima Coffee, Sexy Sexy Bar, 罗伊屋顶花园餐厅, 阿文夜市豆浆油条店, 猪油菜饭, Jiantou Bookstore, Shanghai Home, Jiji Noodle Restaurant, SUBWAY, Fangting Restaurant, local businesses: Shanghai Second-Hand Goods Transaction Market Limited Company, Shanghai Wanshang Zhoujiazui Plants & Pet Market

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.Phone

+86 21 6512 6669

Plan your stay

Pet-friendly Hotels in Shanghai

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Affordable Hotels in Shanghai

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

The Coolest Hotels You Haven't Heard Of (Yet)

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Trending Stays Worth the Hype in Shanghai

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Reviews

Live events

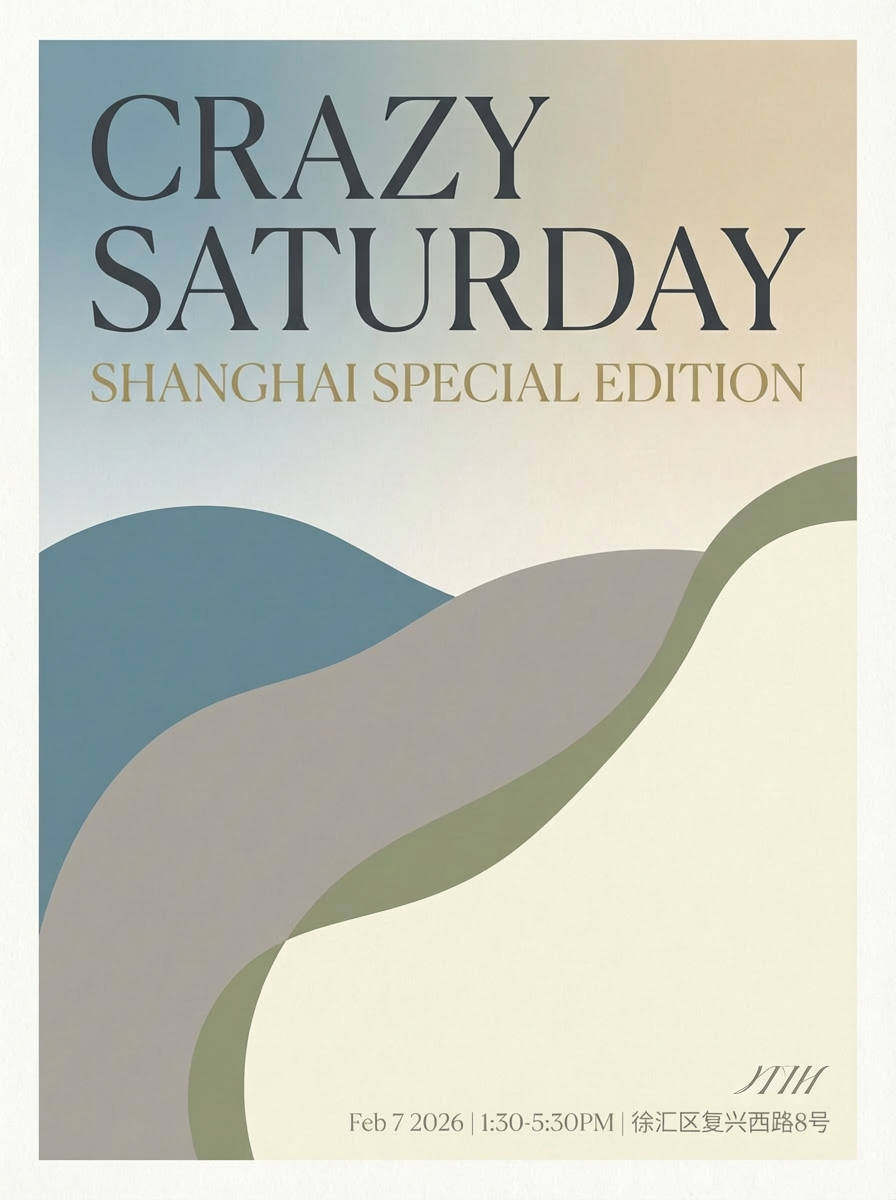

疯狂星期六 上海场

Sat, Feb 7 • 5:30 AM

8 Fu Xing Xi Lu, Xu Hui Qu, Shang Hai Shi, China, 200031

View details

Nearby attractions of Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum

Huoshan Park (North Gate)

Xiahai Temple

North Bund Green Land

宝地广场

Huoshan Park (North Gate)

4.6

(9)

Open 24 hours

Click for details

Xiahai Temple

4.3

(8)

Open 24 hours

Click for details

North Bund Green Land

4.7

(87)

Open 24 hours

Click for details

宝地广场

4.2

(19)

Open 24 hours

Click for details

Nearby restaurants of Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum

Baima Coffee

Sexy Sexy Bar

罗伊屋顶花园餐厅

阿文夜市豆浆油条店

猪油菜饭

Jiantou Bookstore

Shanghai Home

Jiji Noodle Restaurant

SUBWAY

Fangting Restaurant

Baima Coffee

4.7

(2)

Click for details

Sexy Sexy Bar

2.9

(7)

Closed

Click for details

罗伊屋顶花园餐厅

3.0

(1)

Click for details

阿文夜市豆浆油条店

4.0

(2)

Open until 10:00 PM

Click for details

Nearby local services of Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum

Shanghai Second-Hand Goods Transaction Market Limited Company

Shanghai Wanshang Zhoujiazui Plants & Pet Market

Shanghai Second-Hand Goods Transaction Market Limited Company

4.4

(10)

Click for details

Shanghai Wanshang Zhoujiazui Plants & Pet Market

4.1

(11)

Click for details