Isa Khan's Tomb, Delhi things to do, attractions, restaurants, events info and trip planning

Basic Info

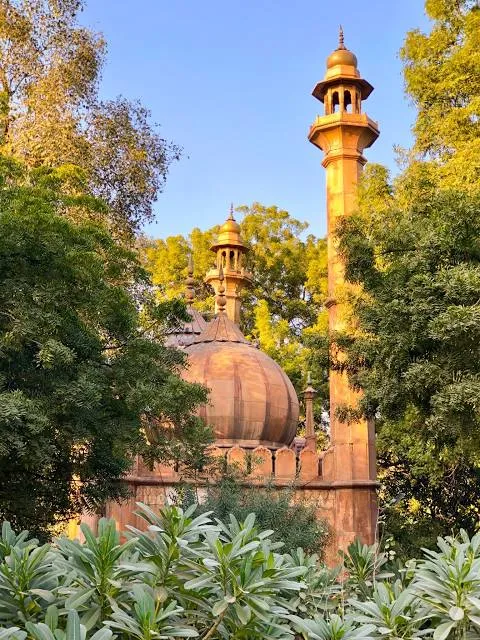

Isa Khan's Tomb, Delhi

Humayun's Tomb complex, Mathura Rd, Nizamuddin, Nizamuddin East, New Delhi, Delhi 110013, India

4.4(1.5K)

Open until 7:00 PM

tickets

Save

spot

spot

Ratings & Description

Info

Cultural

Accessibility

attractions: Sunder Nursery, Humayun’s Tomb, Dargah Nizamuddin Aulia, Ghalib Academy, Humayun's Tomb Entry, Chausath Khambha, Barakhamba Tomb Monument, Ataga khan tomb, Humayun Tomb, Neela Gumbad, restaurants: Karim Hotel, Gulfam Kashmiri Wazwan, ZAKI HOTEL & GUEST HOUSE, Rahim restaurant, Chick Fish Point, Aap Ki Khatir Nizamuddin, Al-fateh Restaurant, Indian Accent, KERALA HOTEL, Cafe Turtle, local businesses: Hazrat Nizamuddin, Sunehri Masjid, Millennium Park Delhi

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.Open hoursSee all hours

Wed6 AM - 7 PMOpen

Plan your stay

Pet-friendly Hotels in Delhi

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Affordable Hotels in Delhi

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

The Coolest Hotels You Haven't Heard Of (Yet)

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Trending Stays Worth the Hype in Delhi

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Reviews

Live events

Taj Mahal Sunrise & Agra Fort Day Tour from Delhi

Sat, Feb 14 • 3:00 AM

New Delhi, Delhi, 110001, India

View details

Old Delhi Food-Temples-Spice Market & Rickshaw

Wed, Feb 11 • 1:00 PM

New Delhi, Delhi, 110006, India

View details

Same Day Taj Mahal & Agra Fort Tour from Delhi

Fri, Feb 13 • 2:30 AM

New Delhi, Delhi, 282001, India

View details

Nearby attractions of Isa Khan's Tomb, Delhi

Sunder Nursery

Humayun’s Tomb

Dargah Nizamuddin Aulia

Ghalib Academy

Humayun's Tomb Entry

Chausath Khambha

Barakhamba Tomb Monument

Ataga khan tomb

Humayun Tomb

Neela Gumbad

Sunder Nursery

4.6

(8.4K)

Open until 9:00 PM

Click for details

Humayun’s Tomb

4.5

(17.7K)

Open 24 hours

Click for details

Dargah Nizamuddin Aulia

4.6

(9.5K)

Open until 10:00 PM

Click for details

Ghalib Academy

4.1

(255)

Open 24 hours

Click for details

Nearby restaurants of Isa Khan's Tomb, Delhi

Karim Hotel

Gulfam Kashmiri Wazwan

ZAKI HOTEL & GUEST HOUSE

Rahim restaurant

Chick Fish Point

Aap Ki Khatir Nizamuddin

Al-fateh Restaurant

Indian Accent

KERALA HOTEL

Cafe Turtle

Karim Hotel

3.9

(2.3K)

$$

Open until 12:00 AM

Click for details

Gulfam Kashmiri Wazwan

3.8

(130)

Closed

Click for details

ZAKI HOTEL & GUEST HOUSE

4.0

(97)

Open until 12:00 AM

Click for details

Rahim restaurant

4.7

(61)

Open until 11:00 PM

Click for details

Nearby local services of Isa Khan's Tomb, Delhi

Hazrat Nizamuddin

Sunehri Masjid

Millennium Park Delhi

Hazrat Nizamuddin

3.8

(18.6K)

Click for details

Sunehri Masjid

4.3

(1.1K)

Click for details

Millennium Park Delhi

4.2

(3.3K)

Click for details