Hess Triangle things to do, attractions, restaurants, events info and trip planning

Basic Info

Hess Triangle

110 7th Ave S, New York, NY 10014

4.7(74)

Open until 12:00 AM

Save

spot

spot

Ratings & Description

Info

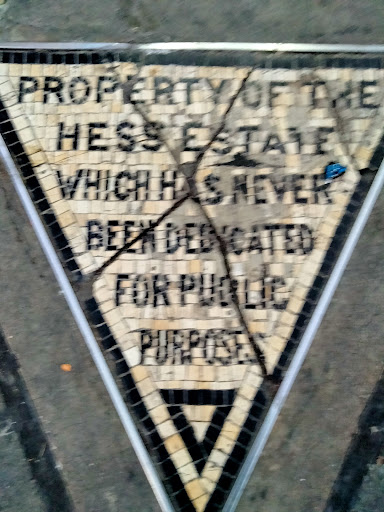

The Hess triangle is a triangular tile mosaic set in a sidewalk in New York City's West Village neighborhood at the corner of Seventh Avenue and Christopher Street. The plaque reads "Property of the Hess Estate which has never been dedicated for public purposes."

Cultural

Off the beaten path

attractions: Stonewall National Monument, Christopher Park, Gay Liberation Monument, Greenwich House Theater, Stonewall National Monument Visitor Center, Lucille Lortel Theatre, Sheridan Square Viewing Garden, Washington Square Park, Axis Theatre Company, Cherry Lane Theatre, restaurants: Boucherie West Village, Via Carota, Smalls Jazz Club, Marie's Crisis Café, The Duplex, Cellar Dog, Arthur's Tavern, Jekyll and Hyde Club, The Stonewall Inn, 787 Coffee, local businesses: QQ Nails & Spa, Heart of Chelsea - West Village, La Virtu Wax Studio, Stonewall National Monument, Bleecker Trading, YARA, TMPL - West Village, West Village Eyecare Associates, Olfactory NYC, Studio Zen New York - Best hair salon in West Village, NYC.

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.Open hoursSee all hours

FriOpen 24 hoursOpen

Plan your stay

Pet-friendly Hotels in New York

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Affordable Hotels in New York

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

The Coolest Hotels You Haven't Heard Of (Yet)

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Trending Stays Worth the Hype in New York

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Reviews

Live events

ARTE MUSEUM: An Immersive Media Art Exhibition

Fri, Feb 27 • 10:00 AM

61 Chelsea Piers, New York, 10011

View details

The Full-Day See It All NYC Tour

Fri, Feb 27 • 9:00 AM

New York, New York, 10019

View details

Taste New York street food with a native guide

Fri, Feb 27 • 1:00 PM

Queens, New York, 11372

View details

Nearby attractions of Hess Triangle

Stonewall National Monument

Christopher Park

Gay Liberation Monument

Greenwich House Theater

Stonewall National Monument Visitor Center

Lucille Lortel Theatre

Sheridan Square Viewing Garden

Washington Square Park

Axis Theatre Company

Cherry Lane Theatre

Stonewall National Monument

4.5

(360)

Closed

Click for details

Christopher Park

4.6

(267)

Closed

Click for details

Gay Liberation Monument

4.4

(58)

Open 24 hours

Click for details

Greenwich House Theater

4.7

(102)

Open 24 hours

Click for details

Nearby restaurants of Hess Triangle

Boucherie West Village

Via Carota

Smalls Jazz Club

Marie's Crisis Café

The Duplex

Cellar Dog

Arthur's Tavern

Jekyll and Hyde Club

The Stonewall Inn

787 Coffee

Boucherie West Village

4.8

(3.6K)

$$$

Closed

Click for details

Via Carota

4.4

(1.4K)

$$$

Closed

Click for details

Smalls Jazz Club

4.6

(1.6K)

$$

Closed

Click for details

Marie's Crisis Café

4.5

(642)

$

Closed

Click for details

Nearby local services of Hess Triangle

QQ Nails & Spa

Heart of Chelsea - West Village

La Virtu Wax Studio

Stonewall National Monument

Bleecker Trading

YARA

TMPL - West Village

West Village Eyecare Associates

Olfactory NYC

Studio Zen New York - Best hair salon in West Village, NYC.

QQ Nails & Spa

4.7

(455)

Click for details

Heart of Chelsea - West Village

5.0

(20)

Click for details

La Virtu Wax Studio

5.0

(178)

Click for details

Stonewall National Monument

4.6

(267)

Click for details