Padiglione della Germania things to do, attractions, restaurants, events info and trip planning

Basic Info

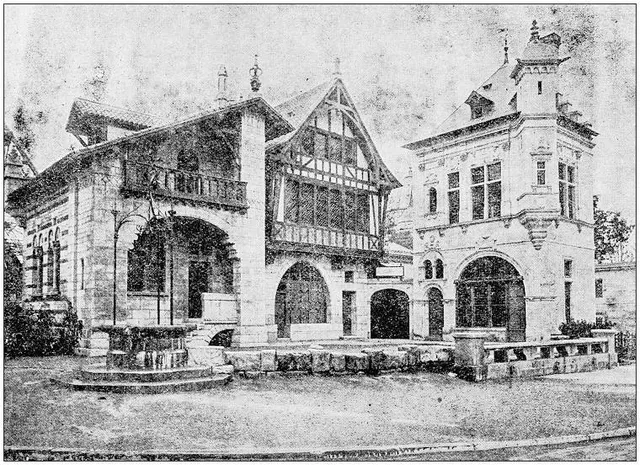

Padiglione della Germania

Giardini della Biennale, 30010 Venezia VE, Italy

3.5(243)

Closed

Save

spot

spot

Ratings & Description

Info

The Barcelona Pavilion, designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Lilly Reich, was the German Pavilion for the 1929 International Exposition in Barcelona, Spain. This building was used for the official opening of the German section of the exhibition.

Cultural

Accessibility

attractions: Giardini della Biennale, Biennale di Venezia - Padiglione Canadese, Parco delle Rimembranze, Pavilion of France, British Pavilion of the Venice Biennale, Padiglione Centrale, Bolivian Pavillion of the Venice Bienal, Nordic Pavilion of the Venice Biennale, Padiglione del Giappone, Belgian Pavilion, restaurants: Osteria da Pampo, Vincent Bar, Ristorante In Paradiso, GIARDIN Food & Art Oasis, Osteria San Isepo, Vecia Gina, Trattoria Dai Fioi, Caffè La Serra, Antica Osteria da Gino, Trattoria Dai Tosi, local businesses: Central Pavilion, Pavilhão da Austrália da Bienal de Veneza, La Biennale di Venezia - Padiglione della Grecia, Pavilhão da Venezuela da Bienal de Veneza, Non solo pane Venezia, Sant'Elena, Venezia Catamaran Cruises, Isola Sant'Elena, La Biennale di Venezia - Israele, Classic Boats Venice - Boat Rentals and Experiences in Venice, Italy

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.Phone

+39 041 521 8711

Website

labiennale.org

Open hoursSee all hours

Mon10 AM - 6 PMClosed

Plan your stay

Pet-friendly Hotels in Venice

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Affordable Hotels in Venice

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

The Coolest Hotels You Haven't Heard Of (Yet)

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Trending Stays Worth the Hype in Venice

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Reviews

Live events

Chiesa di Venezia di Vivaldi: Concerto Le Quattro Stagioni di Vivaldi

Mon, Feb 9 • 7:00 PM

Piazza San Marco, Venezia, 30124

View details

STELLAR-PARTY

Thu, Feb 12 • 7:00 PM

45 Via Fratelli Bandiera, 30175 Venezia

View details

OGNI VENERDI ANDA VENICE HOSTEL - FREE ENTRY

Fri, Feb 13 • 10:00 PM

10 Via Ortigara, 30171 Mestre

View details

Nearby attractions of Padiglione della Germania

Giardini della Biennale

Biennale di Venezia - Padiglione Canadese

Parco delle Rimembranze

Pavilion of France

British Pavilion of the Venice Biennale

Padiglione Centrale

Bolivian Pavillion of the Venice Bienal

Nordic Pavilion of the Venice Biennale

Padiglione del Giappone

Belgian Pavilion

Giardini della Biennale

4.5

(5K)

Open until 12:00 AM

Click for details

Biennale di Venezia - Padiglione Canadese

4.4

(272)

Open until 12:00 AM

Click for details

Parco delle Rimembranze

4.6

(679)

Open until 12:00 AM

Click for details

Pavilion of France

4.2

(107)

Closed

Click for details

Nearby restaurants of Padiglione della Germania

Osteria da Pampo

Vincent Bar

Ristorante In Paradiso

GIARDIN Food & Art Oasis

Osteria San Isepo

Vecia Gina

Trattoria Dai Fioi

Caffè La Serra

Antica Osteria da Gino

Trattoria Dai Tosi

Osteria da Pampo

4.6

(728)

Closed

Click for details

Vincent Bar

4.3

(316)

Open until 12:00 AM

Click for details

Ristorante In Paradiso

3.5

(201)

$$

Closed

Click for details

GIARDIN Food & Art Oasis

4.9

(110)

Open until 12:00 AM

Click for details

Nearby local services of Padiglione della Germania

Central Pavilion

Pavilhão da Austrália da Bienal de Veneza

La Biennale di Venezia - Padiglione della Grecia

Pavilhão da Venezuela da Bienal de Veneza

Non solo pane Venezia

Sant'Elena

Venezia Catamaran Cruises

Isola Sant'Elena

La Biennale di Venezia - Israele

Classic Boats Venice - Boat Rentals and Experiences in Venice, Italy

Central Pavilion

4.5

(570)

Click for details

Pavilhão da Austrália da Bienal de Veneza

4.3

(37)

Click for details

La Biennale di Venezia - Padiglione della Grecia

4.1

(42)

Click for details

Pavilhão da Venezuela da Bienal de Veneza

3.9

(21)

Click for details