Fort Santiago things to do, attractions, restaurants, events info and trip planning

Basic Info

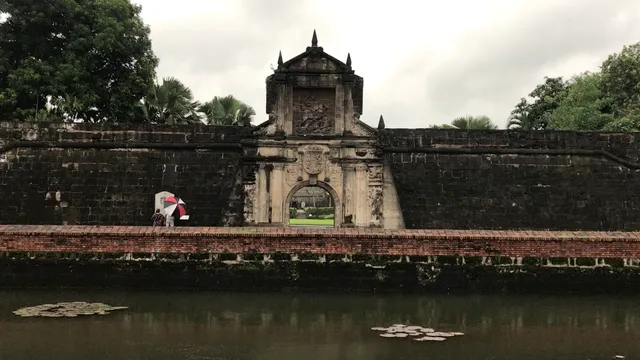

Fort Santiago

Intramuros, Manila, 1002 Metro Manila, Philippines

4.5(4.9K)

Open until 11:00 PM

tickets

Save

spot

spot

Ratings & Description

Info

Fort Santiago, built in 1571, is a citadel built by Spanish navigator and governor Miguel López de Legazpi for the newly established city of Manila in the Philippines. The defense fortress is located in Intramuros, the walled city of Manila. The fort is one of the most important historical sites in Manila.

Cultural

Outdoor

Family friendly

attractions: Rizal Shrine, The Dungeons of Fort Santiago, Plaza de Armas, Plaza Moriones, The Manila Cathedral, Baluarte de San Miguel, Ruins of the American Barracks, Museo de Intramuros, San Agustin Church, Bahay Tsinoy, Museum of Chinese in Philippine Life, restaurants: Figaro Coffee - Intramuros, Max's Intramuros, Chic-Boy, Beanleaf Fort Santiago, Greenwich - Intramuros, La Cathedral Cafe, Belfry Café, Jollibee, Bacolod Chicken House, Chowking, local businesses: Baluarte de Santa Barbara, Palacio del Gobernador, Binondo–Intramuros Bridge, San Agustin Convent Museum, Divisoria Mall Marketing, Liwasang Bonifacio, Eng Bee Tin Chinese Deli, Escolta Street

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.Phone

+63 2 8527 3155

Website

visitfortsantiago.com

Open hoursSee all hours

Mon8 AM - 11 PMOpen

Plan your stay

Pet-friendly Hotels in Manila

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Affordable Hotels in Manila

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

The Coolest Hotels You Haven't Heard Of (Yet)

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Trending Stays Worth the Hype in Manila

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Reviews

Live events

Learn to play golf in Manila

Mon, Feb 9 • 8:00 AM

Pasay, Metro Manila, Philippines

View details

Makati Street Food Experience End in a Rooftop Bar

Mon, Feb 9 • 6:00 PM

Makati, 1210, Metro Manila, Philippines

View details

Hidden Gems of Manila

Mon, Feb 9 • 8:00 AM

Manila, 1012, Metro Manila, Philippines

View details

Nearby attractions of Fort Santiago

Rizal Shrine

The Dungeons of Fort Santiago

Plaza de Armas

Plaza Moriones

The Manila Cathedral

Baluarte de San Miguel

Ruins of the American Barracks

Museo de Intramuros

San Agustin Church

Bahay Tsinoy, Museum of Chinese in Philippine Life

Rizal Shrine

4.7

(148)

Open until 12:00 AM

Click for details

The Dungeons of Fort Santiago

4.6

(100)

Closed

Click for details

Plaza de Armas

4.5

(19)

Open 24 hours

Click for details

Plaza Moriones

4.4

(63)

Open until 5:00 PM

Click for details

Nearby restaurants of Fort Santiago

Figaro Coffee - Intramuros

Max's Intramuros

Chic-Boy

Beanleaf Fort Santiago

Greenwich - Intramuros

La Cathedral Cafe

Belfry Café

Jollibee

Bacolod Chicken House

Chowking

Figaro Coffee - Intramuros

4.2

(114)

Open until 9:00 PM

Click for details

Max's Intramuros

4.0

(221)

Open until 8:00 PM

Click for details

Chic-Boy

3.8

(154)

Open until 11:00 PM

Click for details

Beanleaf Fort Santiago

3.6

(30)

Open until 9:00 PM

Click for details

Nearby local services of Fort Santiago

Baluarte de Santa Barbara

Palacio del Gobernador

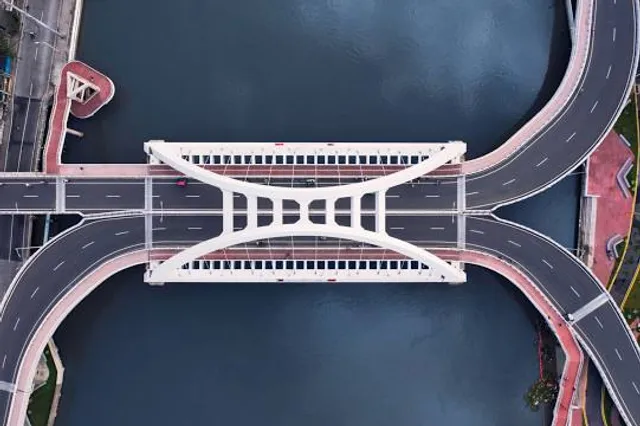

Binondo–Intramuros Bridge

San Agustin Convent Museum

Divisoria Mall Marketing

Liwasang Bonifacio

Eng Bee Tin Chinese Deli

Escolta Street

Baluarte de Santa Barbara

4.5

(16)

Click for details

Palacio del Gobernador

4.5

(73)

Click for details

Binondo–Intramuros Bridge

4.7

(415)

Click for details

San Agustin Convent Museum

4.7

(125)

Click for details