Museum of Vancouver things to do, attractions, restaurants, events info and trip planning

Basic Info

Museum of Vancouver

1100 Chestnut St, Vancouver, BC V6J 3J9, Canada

4.3(983)

Closed

tickets

Save

spot

spot

Ratings & Description

Info

The Museum of Vancouver is a civic history museum located in Vanier Park, Vancouver, British Columbia. The MOV is the largest civic museum in Canada and the oldest museum in Vancouver. The museum was founded in 1894 and went through a number of iterations before being rebranded as the Museum of Vancouver in 2009.

Cultural

Family friendly

Accessibility

attractions: Vanier Park, Vancouver Planetarium, H.R. MacMillan Space Centre, Vancouver Maritime Museum, Hadden Park, Hadden Beach, St. Roch National Historic Site, Elsje Point, Sunset Beach, Burrard Street Bridge, restaurants: Siegel's Bagels, Moltan, Corduroy Restaurant, Cockney Kings Fish & Chips, Juliet's Cafe, Albasha Express Shawarma & Falafel, Kits Beach Coffee, Vera's Burger Shack Kitsilano, Charqui, AnnaLena, local businesses: The Dome, Sunset Beach Park, Vanier Park Parking, Maritime Museum, Heritage Harbour, Granville Island Public Market, Sunset Beach, lululemon Store Support Centre (SSC), Aquatic Centre Ferry Dock, Granville island - Sunshine Nails & Spa

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.Phone

+1 604-736-4431

Website

museumofvancouver.ca

Open hoursSee all hours

Sun10 AM - 5 PMClosed

Plan your stay

Pet-friendly Hotels in Vancouver

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Affordable Hotels in Vancouver

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

The Coolest Hotels You Haven't Heard Of (Yet)

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Trending Stays Worth the Hype in Vancouver

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Reviews

Live events

City highlights walking tour of downtown Vancouver

Sun, Feb 22 • 10:00 AM

Vancouver, British Columbia, V6C 3T4, Canada

View details

Outdoor Photo Session in Vancouver’s Best Spots

Sun, Feb 22 • 9:00 AM

Vancouver, British Columbia, V6C 2W6, Canada

View details

Discover the Lost Souls of Gastown

Sun, Feb 22 • 7:00 PM

Vancouver, British Columbia, V6B 1B6, Canada

View details

Nearby attractions of Museum of Vancouver

Vanier Park

Vancouver Planetarium

H.R. MacMillan Space Centre

Vancouver Maritime Museum

Hadden Park

Hadden Beach

St. Roch National Historic Site

Elsje Point

Sunset Beach

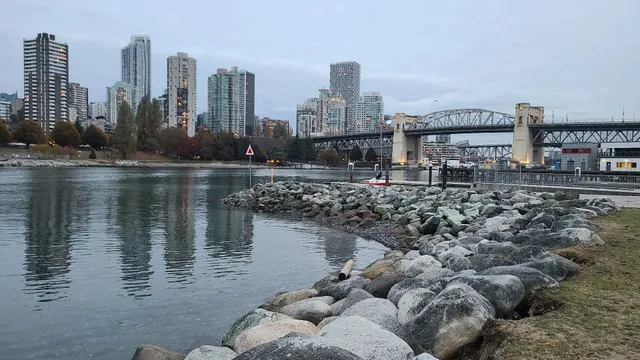

Burrard Street Bridge

Vanier Park

4.6

(970)

Open until 10:00 PM

Click for details

Vancouver Planetarium

4.0

(93)

Closed

Click for details

H.R. MacMillan Space Centre

3.8

(92)

Closed

Click for details

Vancouver Maritime Museum

4.4

(242)

Closed

Click for details

Nearby restaurants of Museum of Vancouver

Siegel's Bagels

Moltan

Corduroy Restaurant

Cockney Kings Fish & Chips

Juliet's Cafe

Albasha Express Shawarma & Falafel

Kits Beach Coffee

Vera's Burger Shack Kitsilano

Charqui

AnnaLena

Siegel's Bagels

4.5

(1.2K)

Open until 12:00 AM

Click for details

Moltan

4.3

(423)

Closed

Click for details

Corduroy Restaurant

4.0

(495)

Click for details

Cockney Kings Fish & Chips

4.8

(351)

Closed

Click for details

Nearby local services of Museum of Vancouver

The Dome

Sunset Beach Park

Vanier Park Parking

Maritime Museum

Heritage Harbour

Granville Island Public Market

Sunset Beach

lululemon Store Support Centre (SSC)

Aquatic Centre Ferry Dock

Granville island - Sunshine Nails & Spa

The Dome

4.1

(109)

Click for details

Sunset Beach Park

4.7

(3.8K)

Click for details

Vanier Park Parking

3.3

(10)

Click for details

Maritime Museum

4.6

(24)

Click for details