Yale Center for British Art things to do, attractions, restaurants, events info and trip planning

Basic Info

Yale Center for British Art

1080 Chapel St, New Haven, CT 06510

4.7(351)

Open 24 hours

Save

spot

spot

Ratings & Description

Info

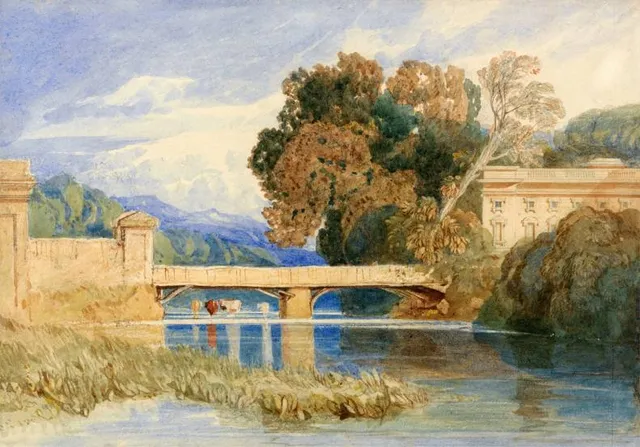

The Yale Center for British Art at Yale University in central New Haven, Connecticut, houses the largest and most comprehensive collection of British art outside the United Kingdom.

Cultural

Family friendly

Accessibility

attractions: Yale University Art Gallery, Yale Repertory Theatre, Shubert Theatre, New Haven Green, Harkness Tower, Yale Old Campus, University Theatre, Trinity on the Green Episcopal Church, The Mead Visitor Center, Branford College, restaurants: Atticus Bookstore Cafe, Louis' Lunch, olea, Geronimo Tequila Bar and Southwest Grill - New Haven, Union League, Harvest Wine Bar & Restaurant, Claire's Corner Copia, Elm City Social, Loose Leaf Boba Company, Book Trader Cafe, local businesses: The Little Salad Shop, Uni-Home Life, Sweatfluence, New Haven, Enson's Menswear, Derek Simpson Goldsmith, Hull's Art Supply & Framing, Yale Center for British Art | Museum Shop, Union League Pâtisserie, Chapel Mini Mart, Merwin's Art Shop

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.Phone

(203) 432-2800

Website

britishart.yale.edu

Plan your stay

Pet-friendly Hotels in New Haven

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Affordable Hotels in New Haven

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

The Coolest Hotels You Haven't Heard Of (Yet)

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Trending Stays Worth the Hype in New Haven

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Reviews

Live events

Caloroso Eatery and Bar

Thu, Feb 26 • 6:00 PM

100 Center Street Shelton, CT 06484

View details

Leprecon Bar Crawl: Connecticuts #1 St. Paddys Event

Sat, Feb 28 • 12:00 PM

216 Crown Street New Haven, CT 06510

View details

Waterbury Murder Mystery: Solve the case!

Sun, Feb 1 • 12:00 AM

Waterbury, 06702

View details

Nearby attractions of Yale Center for British Art

Yale University Art Gallery

Yale Repertory Theatre

Shubert Theatre

New Haven Green

Harkness Tower

Yale Old Campus

University Theatre

Trinity on the Green Episcopal Church

The Mead Visitor Center

Branford College

Yale University Art Gallery

4.8

(1.4K)

Closed

Click for details

Yale Repertory Theatre

4.6

(103)

Open 24 hours

Click for details

Shubert Theatre

4.6

(517)

Open 24 hours

Click for details

New Haven Green

4.1

(1.9K)

Open until 12:00 AM

Click for details

Nearby restaurants of Yale Center for British Art

Atticus Bookstore Cafe

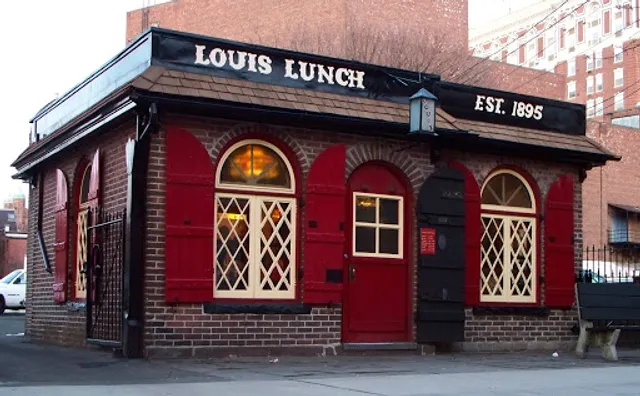

Louis' Lunch

olea

Geronimo Tequila Bar and Southwest Grill - New Haven

Union League

Harvest Wine Bar & Restaurant

Claire's Corner Copia

Elm City Social

Loose Leaf Boba Company

Book Trader Cafe

Atticus Bookstore Cafe

4.4

(513)

$

Closed

Click for details

Louis' Lunch

4.4

(1.3K)

$

Closed

Click for details

olea

4.7

(244)

$$$

Open until 10:00 PM

Click for details

Geronimo Tequila Bar and Southwest Grill - New Haven

4.3

(842)

$$

Open until 1:00 AM

Click for details

Nearby local services of Yale Center for British Art

The Little Salad Shop

Uni-Home Life

Sweatfluence, New Haven

Enson's Menswear

Derek Simpson Goldsmith

Hull's Art Supply & Framing

Yale Center for British Art | Museum Shop

Union League Pâtisserie

Chapel Mini Mart

Merwin's Art Shop

The Little Salad Shop

3.9

(86)

Click for details

Uni-Home Life

4.9

(38)

Click for details

Sweatfluence, New Haven

4.8

(102)

Click for details

Enson's Menswear

4.8

(23)

Click for details