Grande Mosquée de Paris things to do, attractions, restaurants, events info and trip planning

Basic Info

Grande Mosquée de Paris

2bis Pl. du Puits de l'Ermite, 75005 Paris, France

4.5(6.1K)

Open until 12:00 AM

tickets

Save

spot

spot

Ratings & Description

Info

The Grand Mosque of Paris, also known as the Great Mosque of Paris or simply the Paris Mosque, is located in the 5th arrondissement and is one of the largest mosques in France. There are prayer rooms, an outdoor garden, a small library, a gift shop, along with a cafe and restaurant.

Cultural

Accessibility

attractions: Gallery of Evolution, National Museum of Natural History, Gallery of Mineralogy and Geology, Labyrinthe du Jardin des Plantes, Jardin des Plantes, Gloriette de Buffon, Bibliothèque Centrale - Muséum national d'histoire naturelle (MNHN), Arènes de Lutèce, Jardin des Plantes Greenhouses, Serre des forêts tropicales humides, restaurants: Restaurant La Mosquée de Paris, La Table d'Hami, Crible, KE TEA 可茶, Le jardin de Jasmine, Le Jardin des Pâtes, El Picaflor, La Taverne du Cap Vert et du Brésil, Les Petits Pois, Bibie Paris, local businesses: Gran Galería de la Evolución, Hammam de la Grande Mosquée de Paris, Al-Bustane, Pharmacie Monge Notre Dame, Bowling Mouffetard, Ménagerie (Zoológico) del Jardín de las Plantas, Par’Ici, BOÉMI PARIS | EXPERT BALAYAGE | COLORISTE | PARIS 5 📍, Ô Siam Spa, Bulles en Vrac

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.Phone

+33 1 45 35 97 33

Website

grandemosqueedeparis.fr

Open hoursSee all hours

FriClosedOpen

Plan your stay

Pet-friendly Hotels in Paris

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Affordable Hotels in Paris

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

The Coolest Hotels You Haven't Heard Of (Yet)

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Trending Stays Worth the Hype in Paris

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Reviews

Live events

M.C. Escher - Exposition

Fri, Feb 20 • 5:15 PM

11 quai de Conti, 75006

View details

Planète Préhistorique : Dinosaures, L’expérience immersive à l’Atelier des Lumières

Fri, Feb 20 • 5:30 PM

38 Rue Saint-Maur, 75011

View details

Paradox Museum Paris

Fri, Feb 20 • 4:45 PM

38 Boulevard des Italiens, Paris, 75009

View details

Nearby attractions of Grande Mosquée de Paris

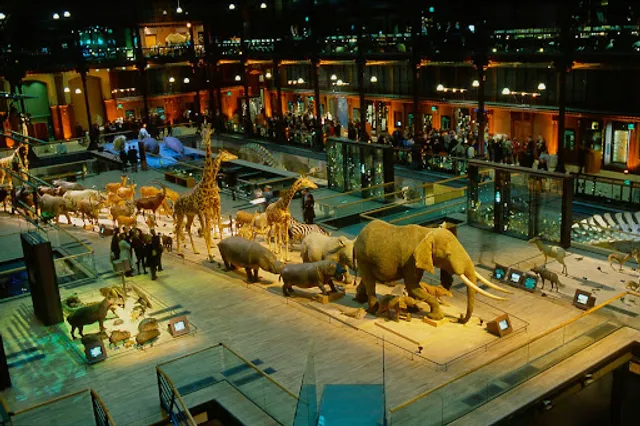

Gallery of Evolution

National Museum of Natural History

Gallery of Mineralogy and Geology

Labyrinthe du Jardin des Plantes

Jardin des Plantes

Gloriette de Buffon

Bibliothèque Centrale - Muséum national d'histoire naturelle (MNHN)

Arènes de Lutèce

Jardin des Plantes Greenhouses

Serre des forêts tropicales humides

Gallery of Evolution

4.6

(6.4K)

Closed

Click for details

National Museum of Natural History

4.5

(3K)

Closed

Click for details

Gallery of Mineralogy and Geology

4.5

(880)

Closed

Click for details

Labyrinthe du Jardin des Plantes

4.4

(189)

Open 24 hours

Click for details

Nearby restaurants of Grande Mosquée de Paris

Restaurant La Mosquée de Paris

La Table d'Hami

Crible

KE TEA 可茶

Le jardin de Jasmine

Le Jardin des Pâtes

El Picaflor

La Taverne du Cap Vert et du Brésil

Les Petits Pois

Bibie Paris

Restaurant La Mosquée de Paris

3.8

(1.7K)

Open until 12:00 AM

Click for details

La Table d'Hami

4.5

(302)

Closed

Click for details

Crible

4.9

(349)

Closed

Click for details

KE TEA 可茶

4.8

(19)

Open until 8:00 PM

Click for details

Nearby local services of Grande Mosquée de Paris

Gran Galería de la Evolución

Hammam de la Grande Mosquée de Paris

Al-Bustane

Pharmacie Monge Notre Dame

Bowling Mouffetard

Ménagerie (Zoológico) del Jardín de las Plantas

Par’Ici

BOÉMI PARIS | EXPERT BALAYAGE | COLORISTE | PARIS 5 📍

Ô Siam Spa

Bulles en Vrac

Gran Galería de la Evolución

4.6

(5.4K)

Click for details

Hammam de la Grande Mosquée de Paris

3.6

(534)

Click for details

Al-Bustane

4.8

(75)

Click for details

Pharmacie Monge Notre Dame

3.4

(1.4K)

Click for details