Atomic Bomb Dome things to do, attractions, restaurants, events info and trip planning

Basic Info

Atomic Bomb Dome

1-10 Otemachi, Naka Ward, Hiroshima, 730-0051, Japan

4.7(12.7K)

Open until 12:00 AM

Save

spot

spot

Ratings & Description

Info

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial, originally the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, and now commonly called the Genbaku Dome, Atomic Bomb Dome or A-Bomb Dome, is part of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park in Hiroshima, Japan and was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996.

Cultural

Educational

attractions: Hiroshima Orizuru Tower, Peace Memorial Park - Hiroshima, Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Hypocenter Monument, Children's Peace Monument, Memorial Tower Dedicated to Mobilized Students, Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall (Atomic Bomb Dome) Fountain Ruins, HIROSHIMA GATE PARK, Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, Clock Tower of Peace, Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall, restaurants: Caffè Ponte, Okonomiyaki Mitchan Sohonten Orizuru tower, Steak AOHIGE, Hiroshima Shuten-doji, Nogami Hanare Hiroshima, Nonta-sushi Kamiyacho, LUCKY BAKERY, Seasonal Dishes and Grilled Food "Tsukiakari", Zwei G-sen, 穴子飯 木村屋本店, local businesses: COIN LUCK 広島店 コインリング作り体験, Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Hypocenter (Shima hospital), Akanece -hiroshima- 手作りリング, EDION HIROSHIMA MAIN STORE, SOGO Hiroshima, Animate Hiroshima, Aioi Bridge (T-Bridge), Sunmall, Dospara Hiroshima, SOUVENIR SELECT HitotoKi

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.Phone

+81 82-504-2898

Website

city.hiroshima.lg.jp

Open hoursSee all hours

MonOpen 24 hoursOpen

Plan your stay

Pet-friendly Hotels in Hiroshima

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Affordable Hotels in Hiroshima

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

The Coolest Hotels You Haven't Heard Of (Yet)

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Trending Stays Worth the Hype in Hiroshima

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Reviews

Live events

Try Japanese traditional archery at Hiroshima Castle

Mon, Feb 23 • 10:00 AM

730-0011, Hiroshima, Hiroshima, Japan

View details

Hiroshima Peace Walking Tour with a local

Mon, Feb 23 • 10:00 AM

730-0031, Hiroshima, Hiroshima, Japan

View details

Miyajima Walk: Itsukushima Shrine 90 minutes

Mon, Feb 23 • 7:30 AM

739-0588, Hiroshima, Hatsukaichi, Japan

View details

Nearby attractions of Atomic Bomb Dome

Hiroshima Orizuru Tower

Peace Memorial Park - Hiroshima

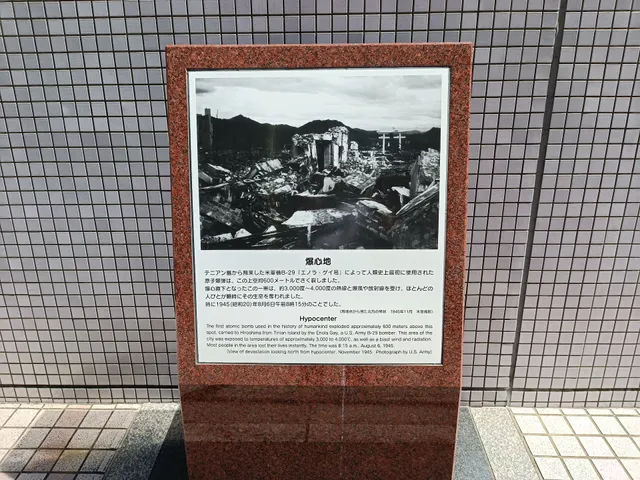

Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Hypocenter Monument

Children's Peace Monument

Memorial Tower Dedicated to Mobilized Students

Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall (Atomic Bomb Dome) Fountain Ruins

HIROSHIMA GATE PARK

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

Clock Tower of Peace

Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall

Hiroshima Orizuru Tower

4.0

(1.8K)

Closed

Click for details

Peace Memorial Park - Hiroshima

4.7

(11.2K)

Open until 12:00 AM

Click for details

Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Hypocenter Monument

4.5

(493)

Open until 12:00 AM

Click for details

Children's Peace Monument

4.7

(670)

Open until 12:00 AM

Click for details

Nearby restaurants of Atomic Bomb Dome

Caffè Ponte

Okonomiyaki Mitchan Sohonten Orizuru tower

Steak AOHIGE

Hiroshima Shuten-doji

Nogami Hanare Hiroshima

Nonta-sushi Kamiyacho

LUCKY BAKERY

Seasonal Dishes and Grilled Food "Tsukiakari"

Zwei G-sen

穴子飯 木村屋本店

Caffè Ponte

4.3

(795)

Closed

Click for details

Okonomiyaki Mitchan Sohonten Orizuru tower

3.9

(200)

Closed

Click for details

Steak AOHIGE

4.7

(545)

Closed

Click for details

Hiroshima Shuten-doji

4.3

(273)

$$

Open until 12:00 AM

Click for details

Nearby local services of Atomic Bomb Dome

COIN LUCK 広島店 コインリング作り体験

Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Hypocenter (Shima hospital)

Akanece -hiroshima- 手作りリング

EDION HIROSHIMA MAIN STORE

SOGO Hiroshima

Animate Hiroshima

Aioi Bridge (T-Bridge)

Sunmall

Dospara Hiroshima

SOUVENIR SELECT HitotoKi

COIN LUCK 広島店 コインリング作り体験

5.0

(876)

Click for details

Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Hypocenter (Shima hospital)

4.4

(306)

Click for details

Akanece -hiroshima- 手作りリング

4.9

(845)

Click for details

EDION HIROSHIMA MAIN STORE

4.2

(1.4K)

Click for details