The National Gallery things to do, attractions, restaurants, events info and trip planning

Basic Info

The National Gallery

Trafalgar Square, London WC2N 5DN, United Kingdom

4.8(21.5K)

Closed

Save

spot

spot

Ratings & Description

Info

The National Gallery is an art museum in Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, in Central London, England. Founded in 1824, in Trafalgar Square since 1838, it houses a collection of over 2,300 paintings dating from the mid-13th century to 1900. The current Director of the National Gallery is Gabriele Finaldi.

Cultural

Accessibility

attractions: Trafalgar Square, National Portrait Gallery, Leicester Square, Garrick Theatre, London Coliseum, His Majesty's Theatre, The Duke of York's Theatre, Theatre Royal Haymarket, The Harold Pinter Theatre, Nelson's Column, restaurants: SOOM Korean Restaurant, Maharaja of India, Steak and Company - Leicester Square, Market Place Food Hall Leicester Square, Prezzo Italian Restaurant London St Martins Lane, Bella Italia - Irving Street, The Chandos, Café in the Crypt, Bancone Covent Garden, Jollibee Leicester Square, local businesses: M&M'S London, Leicester Square, The LEGO® Store Leicester Square, Waterstones, Pall Mall Barbers London | Trafalgar, Cass Art, Watkins Books, tSmart - Piccadilly - Phone Repair Service, Seven Dials Tattoo, Vue Cinema London - West End (Leicester Square)

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.Phone

+44 20 7747 2885

Website

nationalgallery.org.uk

Open hoursSee all hours

Tue10 AM - 6 PMClosed

Plan your stay

Pet-friendly Hotels in London

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Affordable Hotels in London

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

The Coolest Hotels You Haven't Heard Of (Yet)

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Trending Stays Worth the Hype in London

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Reviews

Live events

Explore 30+ London sights

Tue, Feb 17 • 3:00 PM

Greater London, W1J 9BR, United Kingdom

View details

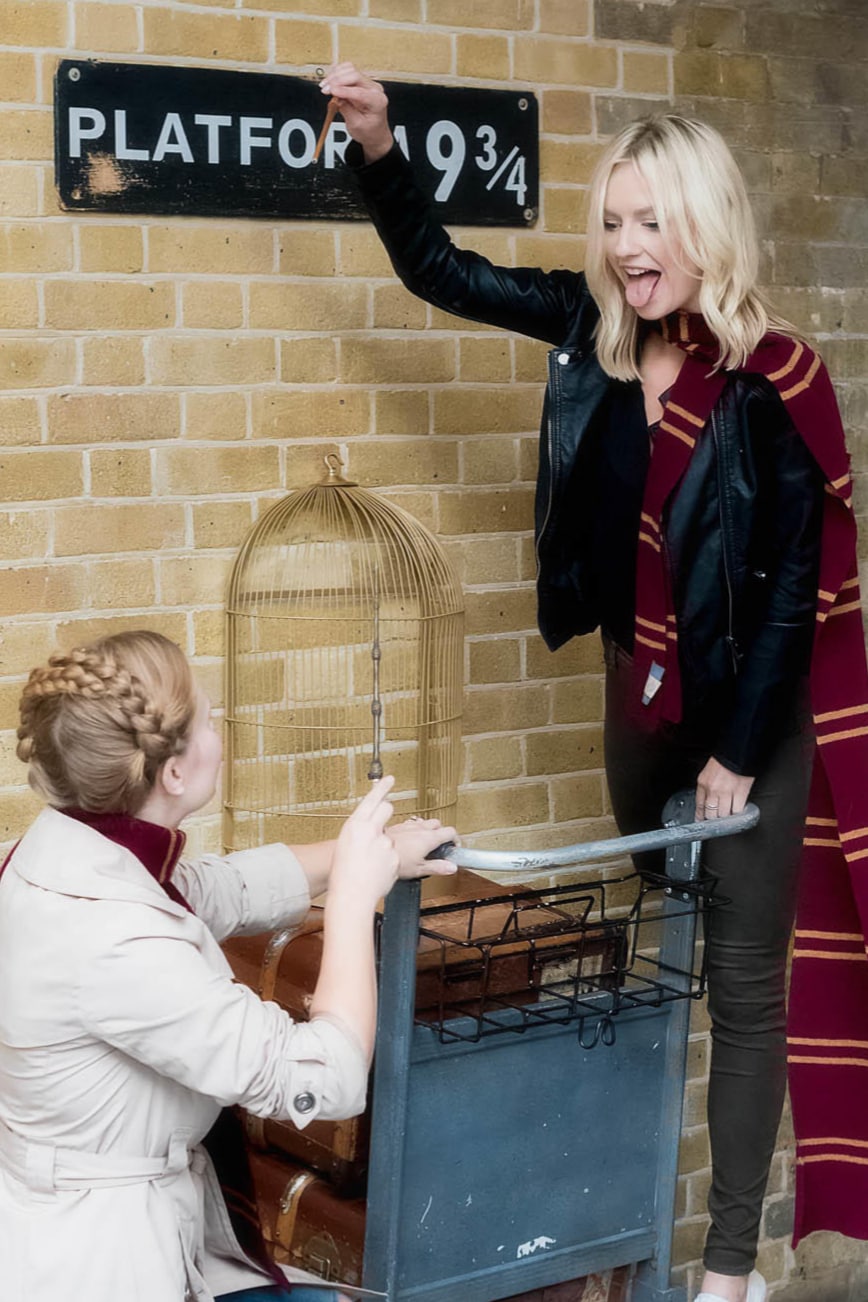

Top-Rated London Harry Potter Tour—Family Friendly

Tue, Feb 17 • 4:00 PM

Greater London, N1 9AP, United Kingdom

View details

London sightseeing walking tour with 30 sights

Fri, Feb 20 • 10:00 AM

Greater London, SW1E 5EA, United Kingdom

View details

Nearby attractions of The National Gallery

Trafalgar Square

National Portrait Gallery

Leicester Square

Garrick Theatre

London Coliseum

His Majesty's Theatre

The Duke of York's Theatre

Theatre Royal Haymarket

The Harold Pinter Theatre

Nelson's Column

Trafalgar Square

4.6

(41.9K)

Open 24 hours

Click for details

National Portrait Gallery

4.7

(6.3K)

Closed

Click for details

Leicester Square

4.5

(9.7K)

Open 24 hours

Click for details

Garrick Theatre

4.6

(1.8K)

Open 24 hours

Click for details

Nearby restaurants of The National Gallery

SOOM Korean Restaurant

Maharaja of India

Steak and Company - Leicester Square

Market Place Food Hall Leicester Square

Prezzo Italian Restaurant London St Martins Lane

Bella Italia - Irving Street

The Chandos

Café in the Crypt

Bancone Covent Garden

Jollibee Leicester Square

SOOM Korean Restaurant

4.8

(110)

Open until 11:00 PM

Click for details

Maharaja of India

4.7

(6.1K)

Open until 12:00 AM

Click for details

Steak and Company - Leicester Square

4.5

(2.7K)

$$

Open until 11:00 PM

Click for details

Market Place Food Hall Leicester Square

4.5

(80)

$

Open until 10:00 PM

Click for details

Nearby local services of The National Gallery

M&M'S London

Leicester Square

The LEGO® Store Leicester Square

Waterstones

Pall Mall Barbers London | Trafalgar

Cass Art

Watkins Books

tSmart - Piccadilly - Phone Repair Service

Seven Dials Tattoo

Vue Cinema London - West End (Leicester Square)

M&M'S London

4.3

(19.4K)

Click for details

Leicester Square

4.5

(7.7K)

Click for details

The LEGO® Store Leicester Square

4.6

(7.2K)

Click for details

Waterstones

4.5

(1.1K)

Click for details

The hit list

Plan your trip with Wanderboat

Welcome to Wanderboat AI, your AI search for local Eats and Fun, designed to help you explore your city and the world with ease.

Powered by Wanderboat AI trip planner.