The Women's Table things to do, attractions, restaurants, events info and trip planning

Basic Info

The Women's Table

175 Elm St, New Haven, CT 06511

4.9(15)

Open until 12:00 AM

Save

spot

spot

Ratings & Description

Info

Cultural

Scenic

attractions: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, New Haven Green, Woolsey Hall, Yale University Art Gallery, The Mead Visitor Center, Harkness Tower, Morse Recital Hall, Whitney Humanities Center, Yale Center for British Art, Branford College, restaurants: Yorkside Pizza & Restaurant, Ashley's Ice Cream, Sherkaan Indian Street Food, Shah's Halal Food - New Haven, Junzi Kitchen 君子食堂耶鲁店 Yale University, New Haven CT|Healthy Authentic Chinese, Maison B Café, Be Berries Food Truck, The Place 2 Be, Pedals Smoothie and Juice Bar, Tomatillo, local businesses: Sterling Memorial Library, Yale Law School, United States Postal Service, The Yale Bookstore, Phil's Barber Shop, Good Nature Market, Apple New Haven, Grey Matter Books, Berkeley College, Urban Outfitters

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.Phone

+7 985 242-81-14

Open hoursSee all hours

FriOpen 24 hoursOpen

Plan your stay

Pet-friendly Hotels in New Haven

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Affordable Hotels in New Haven

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

The Coolest Hotels You Haven't Heard Of (Yet)

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Trending Stays Worth the Hype in New Haven

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Reviews

Live events

Furniture Study Highlights Tour

Fri, Mar 6 • 12:30 PM

900 West Campus Drive West Haven, CT 06516

View details

Leprecon Bar Crawl: Connecticuts #1 St. Paddys Event

Sat, Feb 28 • 12:00 PM

216 Crown Street New Haven, CT 06510

View details

Powerful Voices Open Mic Show - Live Music, Comedy, Poetry+ More!

Thu, Mar 5 • 8:00 PM

Meriden Meriden, CT 06450

View details

Nearby attractions of The Women's Table

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

New Haven Green

Woolsey Hall

Yale University Art Gallery

The Mead Visitor Center

Harkness Tower

Morse Recital Hall

Whitney Humanities Center

Yale Center for British Art

Branford College

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

4.9

(170)

Closed

Click for details

New Haven Green

4.1

(1.9K)

Open until 12:00 AM

Click for details

Woolsey Hall

4.7

(150)

Open 24 hours

Click for details

Yale University Art Gallery

4.8

(1.4K)

Closed

Click for details

Nearby restaurants of The Women's Table

Yorkside Pizza & Restaurant

Ashley's Ice Cream

Sherkaan Indian Street Food

Shah's Halal Food - New Haven

Junzi Kitchen 君子食堂耶鲁店 Yale University, New Haven CT|Healthy Authentic Chinese

Maison B Café

Be Berries Food Truck

The Place 2 Be

Pedals Smoothie and Juice Bar

Tomatillo

Yorkside Pizza & Restaurant

4.5

(530)

$

Open until 11:00 PM

Click for details

Ashley's Ice Cream

4.6

(254)

$

Open until 10:00 PM

Click for details

Sherkaan Indian Street Food

4.3

(591)

$$

Open until 10:00 PM

Click for details

Shah's Halal Food - New Haven

4.8

(116)

$

Open until 3:00 AM

Click for details

Nearby local services of The Women's Table

Sterling Memorial Library

Yale Law School

United States Postal Service

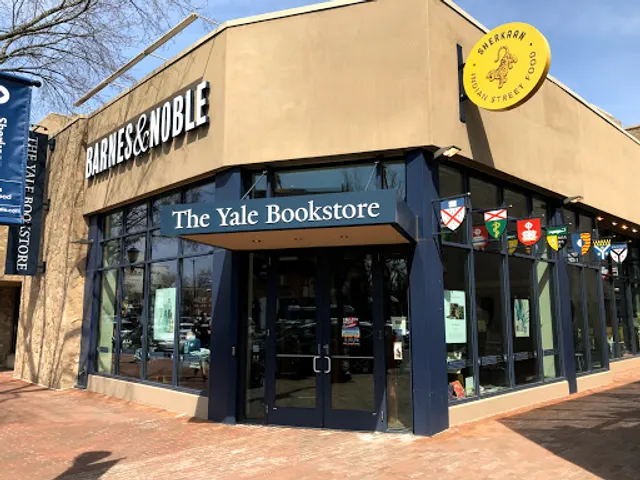

The Yale Bookstore

Phil's Barber Shop

Good Nature Market

Apple New Haven

Grey Matter Books

Berkeley College

Urban Outfitters

Sterling Memorial Library

4.8

(124)

Click for details

Yale Law School

4.4

(70)

Click for details

United States Postal Service

2.3

(119)

Click for details

The Yale Bookstore

4.5

(847)

Click for details