Old Royal Palace things to do, attractions, restaurants, events info and trip planning

Basic Info

Old Royal Palace

Třetí nádvoří Pražského hradu 48, 119 00 Praha 1-Hradčany, Czechia

4.2(887)

Closed

tickets

Save

spot

spot

Ratings & Description

Info

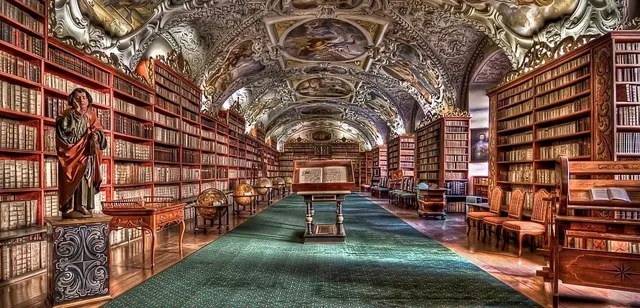

The Old Royal Palace is part of the Prague Castle, Czech Republic. Its history dates back to the 12th century and it is designed in the Gothic and Renaissance styles. Its Vladislav Hall is used for inaugurations, being the most important representative hall in the country. It is also home to a copy of the Czech crown.

Cultural

Scenic

Family friendly

Accessibility

attractions: Prague Castle, St. Vitus Cathedral, St. George's Basilica, The Golden Lane, Great South Tower, Obelisk at Prague Castle, Matthias Gate, Lobkowicz Palace, Story of Prague Castle, Zahrada Na valech, restaurants: Medieval Tavern "U Krále Brabantského", Bistro U Kanovníků, Restaurace U Mlynáře, Vikárka Restaurant, Lore Malastrana, U Tří jelínků, Kuchyň, U Kocoura, U Glaubiců, The Three Fiddles Irish Pub, local businesses: Zlatá ulička u Daliborky, Castle Garden, Golden Lane, Waldstein Palace (Wallenstein Palace), Toy Museum, Fragnerova pharmacy Black Eagle, Galería Nacional de Praga – Palacio Schwarzenberský, Kostel Panny Marie Matky ustavičné pomoci a sv. Kajetána, Ledebur-Garten, Café HAMU

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.Phone

+420 224 373 584

Website

hrad.cz

Open hoursSee all hours

Thu9 AM - 5 PMClosed

Plan your stay

Pet-friendly Hotels in Prague

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Affordable Hotels in Prague

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

The Coolest Hotels You Haven't Heard Of (Yet)

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Trending Stays Worth the Hype in Prague

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Reviews

Live events

The Plague Doctor of Prague

Sat, Feb 28 • 8:00 PM

110 00, Prague 1, Czechia

View details

One Tour To Rule Them All ✌

Fri, Feb 27 • 10:30 AM

118 00, Prague 1, Czechia

View details

Nearby attractions of Old Royal Palace

Prague Castle

St. Vitus Cathedral

St. George's Basilica

The Golden Lane

Great South Tower

Obelisk at Prague Castle

Matthias Gate

Lobkowicz Palace

Story of Prague Castle

Zahrada Na valech

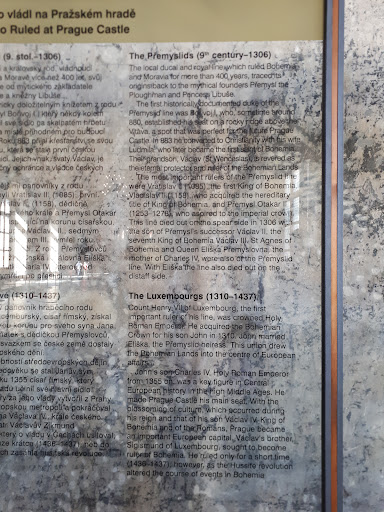

Prague Castle

4.7

(59.2K)

Open until 10:00 PM

Click for details

St. Vitus Cathedral

4.8

(30.4K)

Closed

Click for details

St. George's Basilica

4.4

(1.2K)

Open 24 hours

Click for details

The Golden Lane

4.4

(8.2K)

Closed

Click for details

Nearby restaurants of Old Royal Palace

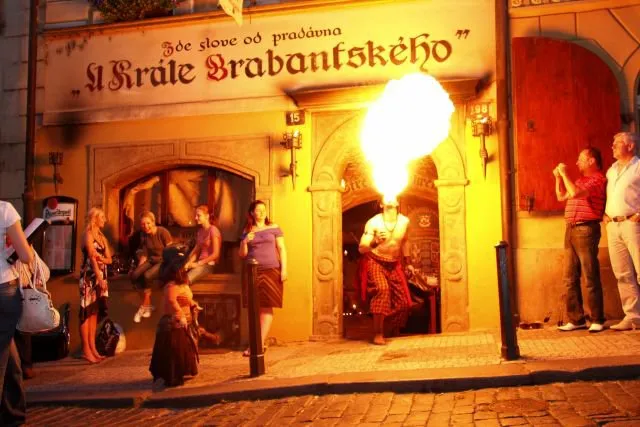

Medieval Tavern "U Krále Brabantského"

Bistro U Kanovníků

Restaurace U Mlynáře

Vikárka Restaurant

Lore Malastrana

U Tří jelínků

Kuchyň

U Kocoura

U Glaubiců

The Three Fiddles Irish Pub

Medieval Tavern "U Krále Brabantského"

4.6

(3K)

$$

Open until 11:00 PM

Click for details

Bistro U Kanovníků

4.5

(425)

Closed

Click for details

Restaurace U Mlynáře

4.5

(2.1K)

$

Open until 10:00 PM

Click for details

Vikárka Restaurant

4.1

(231)

Open until 6:00 PM

Click for details

Nearby local services of Old Royal Palace

Zlatá ulička u Daliborky

Castle Garden

Golden Lane

Waldstein Palace (Wallenstein Palace)

Toy Museum

Fragnerova pharmacy Black Eagle

Galería Nacional de Praga – Palacio Schwarzenberský

Kostel Panny Marie Matky ustavičné pomoci a sv. Kajetána

Ledebur-Garten

Café HAMU

Zlatá ulička u Daliborky

4.1

(499)

Click for details

Castle Garden

4.5

(776)

Click for details

Golden Lane

4.3

(248)

Click for details

Waldstein Palace (Wallenstein Palace)

4.6

(1.1K)

Click for details