National Showa Memorial Museum things to do, attractions, restaurants, events info and trip planning

Basic Info

National Showa Memorial Museum

1 Chome-6-1 Kudanminami, Chiyoda City, Tokyo 102-0074, Japan

4.0(675)

Open until 12:00 AM

tickets

Save

spot

spot

Ratings & Description

Info

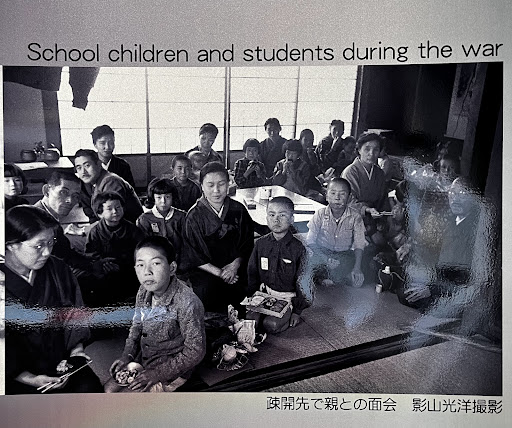

The National Showa Memorial Museum is a national museum in Chiyoda, Tokyo, Japan, managed by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The museum is commonly referred to as the "Showakan" and primarily displays items illustrating the lifestyles of the Japanese people during and after World War II.

Cultural

Accessibility

Family friendly

attractions: Nippon Budokan, Tsukudo Shrine, Kita-no-maru Park, Tayasu-mon Gate, Shōkei-kan, Kudanzaka Park, Science and Technology Museum, Chiyoda City Tourism Association, Shimizumon Gate, Yasukuni-jinja Shrine, restaurants: VMG Café Kudan Kaikan Terrace, Royal Host Kudanshita, Starbucks Coffee - Kitanomaru Square, Kudanshita Torifuku, Warayakiya Kudanshita, Chūkasoba Senmon Tanaka Sobaten Kudanshita, McDonald's Kudanshita, Starbucks Coffee - Kudanshita, Versailles No Buta Kudanshita, Café de Crié - Kudanshita, local businesses: Kudanshita Station, Yasuni Shrine - the First Torii, 日本武道館 普及課, Embassy of India, Manaita Bridge, UTSUWA HANADA, Shueisha, Hatsunemori Shrine Gishikiden, TUAT Science Museum, Chidorigafuchi Boat Pier

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.Phone

+81 3-3222-2577

Website

showakan.go.jp

Open hoursSee all hours

Tue10 AM - 5:30 PMOpen

Plan your stay

Pet-friendly Hotels in Tokyo

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Affordable Hotels in Tokyo

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

The Coolest Hotels You Haven't Heard Of (Yet)

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Trending Stays Worth the Hype in Tokyo

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Reviews

Live events

Explore Tokyo’s music scene with an insider

Thu, Feb 19 • 8:00 AM

150-0043, Tokyo Prefecture, Shibuya, Japan

View details

Toshi Experience World’s largest fish market tour

Tue, Feb 17 • 12:00 PM

135-0061, Tokyo Prefecture, Koto City, Japan

View details

TYFFONIUM お台場:Fluctus (フラクタス)

Tue, Feb 17 • 4:30 PM

東京都江東区青海1丁目1−10 ダイバーシティ東京プラザ5F (1-1-10, Aomi, Koto-Ku, Tokyo DiverCity Tokyo Plaza 5F), 135-0064

View details

Nearby attractions of National Showa Memorial Museum

Nippon Budokan

Tsukudo Shrine

Kita-no-maru Park

Tayasu-mon Gate

Shōkei-kan

Kudanzaka Park

Science and Technology Museum

Chiyoda City Tourism Association

Shimizumon Gate

Yasukuni-jinja Shrine

Nippon Budokan

4.4

(2.7K)

Open until 5:30 PM

Click for details

Tsukudo Shrine

4.0

(270)

Open until 12:00 AM

Click for details

Kita-no-maru Park

4.2

(1.7K)

Open until 12:00 AM

Click for details

Tayasu-mon Gate

4.3

(176)

Open until 12:00 AM

Click for details

Nearby restaurants of National Showa Memorial Museum

VMG Café Kudan Kaikan Terrace

Royal Host Kudanshita

Starbucks Coffee - Kitanomaru Square

Kudanshita Torifuku

Warayakiya Kudanshita

Chūkasoba Senmon Tanaka Sobaten Kudanshita

McDonald's Kudanshita

Starbucks Coffee - Kudanshita

Versailles No Buta Kudanshita

Café de Crié - Kudanshita

VMG Café Kudan Kaikan Terrace

4.7

(781)

Open until 8:00 PM

Click for details

Royal Host Kudanshita

3.5

(363)

Open until 10:00 PM

Click for details

Starbucks Coffee - Kitanomaru Square

3.8

(230)

Open until 10:00 PM

Click for details

Kudanshita Torifuku

3.9

(324)

$$

Closed

Click for details

Nearby local services of National Showa Memorial Museum

Kudanshita Station

Yasuni Shrine - the First Torii

日本武道館 普及課

Embassy of India

Manaita Bridge

UTSUWA HANADA

Shueisha

Hatsunemori Shrine Gishikiden

TUAT Science Museum

Chidorigafuchi Boat Pier

Kudanshita Station

3.6

(350)

Click for details

Yasuni Shrine - the First Torii

4.5

(269)

Click for details

日本武道館 普及課

4.3

(28)

Click for details

Embassy of India

3.5

(222)

Click for details