Trajan's Column things to do, attractions, restaurants, events info and trip planning

Basic Info

Trajan's Column

Via dei Fori Imperiali, 00187 Roma RM, Italy

4.8(2.1K)

Open 24 hours

tickets

Save

spot

spot

Ratings & Description

Info

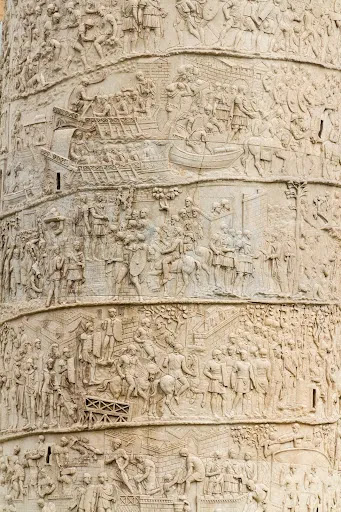

Trajan's Column is a Roman triumphal column in Rome, Italy, that commemorates Roman emperor Trajan's victory in the Dacian Wars. It was probably constructed under the supervision of the architect Apollodorus of Damascus at the order of the Roman Senate. It is located in Trajan's Forum, north of the Roman Forum.

Cultural

Accessibility

attractions: Altare della Patria, Piazza Venezia, Monument to Victor Emmanuel II, Le Domus Romane di Palazzo Valentini, Trajan Forum, Imperial Fora, Mercati di Traiano Museo dei Fori Imperiali, Palazzo Bonaparte, Museo delle Cere, Chiesa di Santa Maria di Loreto, restaurants: LA LEGGERA Pizzeria Restaurant - Piazza Venezia, Oro Bistrot, Nonno Melo, Grano la cucina di Traiano, Panna&Liquirizia, Caffetteria Italia al Vittoriano, Nag's Head Scottish Pub Roma, Ristorante Terre & Domus, Gelateria la fragola, Ristorante Pizzeria Forno A Legna 12 Apostoli, local businesses: Campidoglio, Palacio Colonna, Doria Pamphili Gallery, Souvenir Roma, Giardini di Palazzo Venezia, Capitoline Hill, Via dei Fori Imperiali, Tonin Casa, Tartuffo's Market, Teatro Marcello

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.

Learn more insights from Wanderboat AI.Website

colosseo.it

Plan your stay

Pet-friendly Hotels in Rome

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Affordable Hotels in Rome

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

The Coolest Hotels You Haven't Heard Of (Yet)

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Trending Stays Worth the Hype in Rome

Find a cozy hotel nearby and make it a full experience.

Reviews

Live events

LUNA: A Journey to the Moon – un’esperienza immersiva in realtà virtuale a Roma

Wed, Feb 25 • 4:00 PM

Via Trionfale, 7400, Roma, 00136

View details

Vatican & St Peters Basilica: unlock the wonders

Wed, Feb 25 • 1:00 PM

00192, Rome, Lazio, Italy

View details

Chaos Lab Roma

Fri, Feb 27 • 4:30 PM

P.za di S. Giovanni in Laterano 74, 00185

View details

Nearby attractions of Trajan's Column

Altare della Patria

Piazza Venezia

Monument to Victor Emmanuel II

Le Domus Romane di Palazzo Valentini

Trajan Forum

Imperial Fora

Mercati di Traiano Museo dei Fori Imperiali

Palazzo Bonaparte

Museo delle Cere

Chiesa di Santa Maria di Loreto

Altare della Patria

4.8

(24.7K)

Closed

Click for details

Piazza Venezia

4.7

(20.2K)

Open until 12:00 AM

Click for details

Monument to Victor Emmanuel II

4.8

(25K)

Closed

Click for details

Le Domus Romane di Palazzo Valentini

4.7

(984)

Open until 12:00 AM

Click for details

Nearby restaurants of Trajan's Column

LA LEGGERA Pizzeria Restaurant - Piazza Venezia

Oro Bistrot

Nonno Melo

Grano la cucina di Traiano

Panna&Liquirizia

Caffetteria Italia al Vittoriano

Nag's Head Scottish Pub Roma

Ristorante Terre & Domus

Gelateria la fragola

Ristorante Pizzeria Forno A Legna 12 Apostoli

LA LEGGERA Pizzeria Restaurant - Piazza Venezia

5.0

(67)

Closed

Click for details

Oro Bistrot

4.4

(993)

$$$$

Open until 11:00 PM

Click for details

Nonno Melo

4.4

(803)

Open until 1:00 AM

Click for details

Grano la cucina di Traiano

4.7

(1.4K)

Closed

Click for details

Nearby local services of Trajan's Column

Campidoglio

Palacio Colonna

Doria Pamphili Gallery

Souvenir Roma

Giardini di Palazzo Venezia

Capitoline Hill

Via dei Fori Imperiali

Tonin Casa

Tartuffo's Market

Teatro Marcello

Campidoglio

4.7

(7.8K)

Click for details

Palacio Colonna

4.8

(849)

Click for details

Doria Pamphili Gallery

4.6

(2.5K)

Click for details

Souvenir Roma

4.7

(78)

Click for details

The hit list

Plan your trip with Wanderboat

Welcome to Wanderboat AI, your AI search for local Eats and Fun, designed to help you explore your city and the world with ease.

Powered by Wanderboat AI trip planner.